Home » Business » Nayla Comair-Obeid, an Inspiring Journey of Twenty-Five Years of Advocacy, Education and Excellence

Business

Nayla Comair-Obeid, an Inspiring Journey of Twenty-Five Years of Advocacy, Education and Excellence

Published

3 years agoon

By

Huda Az

Interviewed by: Fatima Omrani

Because women form half of the society, and because they work hand in hand with men in all forums, Arabisk London’s coverage of male and female entrepreneurs would not be complete without the presence of the most amazing pioneering women in all fields. Thus, Arabisk London had the opportunity to host the human rights professor, Nayla Comair-Obeid, in an exclusive interview to talk about her scientific and professional career that is full of significant achievements.

Who is Prof. Dr. Nayla Comair-Obeid?

I am a lawyer and law professor. I am the founding partner of Obeid & Partners Law Firm with offices in Beirut, Paris, and Dubai, and am a member of 3VB in London. I have both the Lebanese and French nationalities, and this is where I find my message: seeking to bring legal cultures closer to one another, the western with the eastern, and especially the Arab ones.

Throughout my career, I have held and continue to hold preeminent positions in many major international legal, judicial and economic institutions. In June 2022, I was elected Vice Chair of the International Chamber of Commerce (ICC). I had been a member of its Executive Board since 2019. I was also recently elected Vice Chair of the Arbitration Committee in the International Bar Association (IBA) and member of the International Council for Commercial Arbitration (ICCA) Governing Board. I am Trustee of the Cairo Regional Centre for International Commercial Arbitration (CRCICA), member of China’s International Commercial Expert Committee of the Supreme People’s Court, and a former member of the LCIA Court in London.

In 2017, I was elected President of the Chartered Institute of Arbitrators (CIArb) in London, and was the first Lebanese, Arab or Middle Eastern person to hold this position since the establishment of the Institute in London in 1915. CIArb was granted a royal charter by Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II in 1979 and later became the first leading professional international institution in promoting the dissemination of arbitration and alternative dispute resolution methods. CIArb also aims to spread the culture of arbitration and educate the arbitrators on the primary qualities they should have such as credibility, neutrality and specialised scientific knowledge.

At the time, all 14,000 members of the Institute, composed of international arbitrators and lawyers in all 5 continental branches of the Institute elected me as president of CIArb. That is 37 branches in 133 countries around the world. I appreciate their trust.

Additionally, I was nominated by the Secretary-General of the United Nations, Mr. Kofi Annan at the time, as a member of the United Nations Compensation Commission in Geneva, and was the only woman in the Commission.

Throughout my career, I have been appointed by parties, institutions and international arbitration centres in more than 150 domestic and international arbitrations as chairperson, sole arbitrator, co-arbitrator or expert.

As a university Professor, I have sought to spread the culture of international law for more than twenty-five years now.

Your academic parcours is very significant. Could you tell us about your academic qualifications?

My academic journey started in 1974 when I got my Master’s degree and Postgraduate Degree in Lebanese and French Law from the two universities of Jean Moulin Lyon III University (France) and Saint Joseph University of Beirut (Lebanon).

In 1994, I obtained a Ph.D. in Business Law from Paris II Panthéon-Assas University. I continue to learn and grow, especially in my practice areas, namely arbitration, civil law, international commercial law, commercial contracts in Islamic and Middle Eastern legislations and Islamic banks.

You founded Obeid Law Firm in 1987. How did you pursue this endeavour? And why law?

There is no doubt that the first steps in a chosen journey are the hardest. Embarking in the world of law and arbitration was not a spur-of-the-moment decision but a daily endeavour which started back in my school years. My ambition always pushed me towards establishing the rule of law, justice, respect of human rights and dignity. That went in line with the conviction that for Lebanon to rise from its set-backs, it has to attract international investments. Only then will it become an international centre for finance, services and tourism. To fulfil this purpose, we need to establish a conflict-solving culture through promoting the role of arbitration courts in resolving conflicts, especially those related to international investments. In addition, it is essential to strengthen the independence of the judiciary, helping judges be receptive to arbitration and be supportive of facilitating the procedure and making this method of dispute resolution effective. I believe in the sacred mission of lawyers and the task of the arbitrator and the mediator in creating a culture of peace and amicable resolution of conflicts. Here, I would like to quote Serge Lazareff, an international arbitrator, who says:

“Arbitration is a way to settle dispute between gentlemen in a gentlemanly manner.”

I took the decision to establish Obeid Law Firm in the middle of the war in Lebanon. It was in direct opposition to the “rage movement” which was sweeping over Lebanon at the time. This latter movement stood for chaos, the law of the jungle and disrespect of human rights and international conventions. I believed this was especially important since Lebanon itself took part in drafting the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in the UN.

This established the conviction to start a law firm with the hope that I could highlight the role of the Lebanese woman in creating peace and consolidating the principles of justice and law. What made my conviction stronger was the support and encouragement of my family that believed in humankind, in equality between men and women and in equality of opportunities. My late father, George Comair (Major General and Medical Doctor in the Lebanese Army), along with my mother drummed into us a sense of national responsibility. He believed in our abilities and launched us into life armed with science and knowledge. That is our most precious asset and treasure!

My conviction increased with the support of my husband and my family. This enabled me to embark into the world of law and to overcome all the challenges.

You quickly integrated the world of law practitioners and distinguished yourself in it. You have a professional career that dates back almost 40 years. Tell us more about the most prominent stages in your career and what shaped Dr. Nayla’s personality today?

My career was built on the three pillars: lawyering, arbitration – i.e. special courts – and teaching.

As a lawyer, I got attracted to the profession’s various fields, long history and core message of achieving justice by expressing a legal opinion and defending rights. This message is in fact a performance of a public service, namely the establishment of the rule of law and the building of institutions. In this spirit, I gained the trust of international companies to pursue their cases in Lebanon and abroad.

As for arbitration, this is a means of resolving disputes through private justice. At the basis of this is a contractual consent to go to arbitration. The arbitrator chosen by the parties or independent international arbitration institutions should have integrity and impartiality, as well as experience and knowledge of procedural rules to resolve a given dispute by issuing an arbitral award to settle the case. Its importance comes from the fact that all states that signed the New York Arbitration Convention are obliged to enforce these arbitral awards provided basic requirements are met. Hence, international investments are activated, and investors are assured of starting an investment related to global trade where countries take into account the culture of arbitration and alternative means of resolving disputes.

When it comes to teaching, I would like to go back in time to 1994. I was eager to introduce arbitration in the education curriculum at Law Schools in Arab countries, through lectures and conferences I held at the League of Arab States concerning the future of arbitration in the Arab world and the importance of introducing arbitration to higher education curricula. That was part of my mission to make the most out of my international positions to spread education and legal culture. The start was with the National Lebanese University, as well as the Holy Spirit University of Kaslik, where this new subject on arbitration was taught. Then, it was introduced to various Law Faculties in other universities. Thus, Lebanon was the first Arab country to teach arbitration. Lebanon was the first Arab country to teach arbitration in its faculties, helping judges, lawyers and students be open to arbitration and learn how to deal with arbitration procedures and domestic and international arbitral awards. Since 1994, I have lectured on international commercial arbitration in many universities and institutions, including the Lebanese Judicial Institute, the University of Paris II – Panthéon-Assas and the University of Oxford in the UK. I have also organised many training courses and trained a large number of judges in various Arab countries such as Saudi Arabia, Qatar, United Arab Emirates, Jordan, Algeria, Syria and Lebanon. I believe in the importance of spreading the culture of arbitration and alternative means of resolving disputes in the Arab world and the upbringing of the arbitrator on the traits they ought to embrace. It is vital to establish a network between arbitrators and arbitration institutions abroad, as well as cooperation between the judiciary (public justice) and arbitration (private justice).

One of the most prominent stages of my career was my election in 2017 as President of the Chartered Institute of Arbitrators (CIArb) in London. The most notable thing during the presidency of the Institute was arranging for three international conferences under the title of: The Synergy and Divergence between Civil Law and Common Law in International Arbitration.

Three flagship conferences were organised: (i) the UAE for Asian and Arab countries in March 2017, in the presence of Arab Ministers of Justice, the Higher Judicial Councils and Supreme Courts, (ii) in Johannesburg – South Africa for the African continent in July 2017 and (iii) in Paris for the European continent in December 2017.

These conferences brought together a group of jurists which included ministers of justice, judges, lawyers and international arbitrators, and we discussed the reality of legislation and compatibility with international arbitration. Moreover, we had numerous meetings with ministers of justice in Hong Kong, Nigeria, UK, China and various Arab countries. We arranged workshops and training sessions to promote the culture of arbitration. We also expressed our legal opinion upon our review and discussion of the most significant international and Arab arbitration legislations recently issued, including the UAE, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Syria, India, Korea and others.

In January 2018, we launched from Beirut an international symposium with the London Court of International Arbitration (LCIA) titled “In-Crisis and Post-Crisis Dispute Management and Resolution”. This was with the participation of the LCIA Director General, Dr. Jacomijn J van Haersolte-van Hof and the Deputy Chairman of the LCIA Board, Christopher Style QC. In the symposium, we spoke about economic, financial and legal mechanisms to attract investments and reconstruction.

This is what I have always strived and am still striving to achieve, as my mission is to promote the culture of arbitration and to transform countries into forums where various economic and legal matters can be discussed and into hubs for attracting international investments. The basis is to strengthen the bridges of communication and create harmony between the legal cultures in civil, common and Islamic law.

All these stages and steps made me proud of what I believe in. I am especially proud when I see my students holding prestigious jobs at international law firms and arbitration firms and economic and arbitral institutions worldwide. It must be noted that Lebanon ranks first in terms of the number of arbitrators and lawyers among its nationals appointed in arbitration cases in the Middle East.

Dr. Nayla, you have demonstrated a strong influence in major positions you occupied in the legal world. You have actively participated in a role or another in more than 150 international arbitrations and represented important government entities. Furthermore, you have been a member of prestigious international institutions and committees. Attaining this rank was certainly not easy. What do you think is the secret of excellence in legal work? And how did you develop your experience in legal work?

In order to succeed in choosing a career, one must first be passionate about it. Our choices may be spur-of-the-moment choices or may be influenced by a person we look up to, but we need passion. When I chose the legal field, I promised myself that I would not spare any effort to develop my legal knowledge. I took part in many international conferences and trainings that would enhance my technical and professional experience. As a scholar, I authored numerous publications covering problematic issues in a range of legal fields including international law, investment, insurance, banking disputes, amongst others.

The secret of success lies in consistency and perseverance against all odds. A lawyer has to be a non-stop researcher to meet all developments and stay acquainted with the issues of today’s world, especially after the Covid-19 pandemic. I work hard to examine every detail in regulations, memoranda, decisions and arbitral awards. I also believe in communication and constructive dialogue. I never settled or rested on my laurels, but rather I keep striving to succeed.

You have plenty of publications in law. Could you introduce us to some?

The most notable books I have authored include:

“Arbitration in Lebanese Law”, a comparative study, issued in 1999 from Bruylant Publishers in Belgium and Delta in Beirut, in English and French (“L’Arbitrage en Droit Libanais”).

“The Law of Business Contracts in the Arab Middle East”, Kluwer Law International, London, May 1996.

“Les Contrats en Droit Musulman des Affaires”, Economica, Paris, 1995.

I have also published numerous articles, research papers and studies which have been published in the most prominent international law journals. I am frequently invited to give lectures and speak as a leading expert in my field.

You have been rewarded with many awards of appreciation. You have been chosen as a leading lawyer in the field of arbitration in Lebanon by “Who’s Who Legal” international legal experts in commercial law. You have also been named a leading lawyer in the field of dispute resolution in Lebanon by Chambers Global. How would you describe these experiences?

Of course, all of these notable mentions have strengthened my belief that those who work hard, believe in their capabilities and develop themselves can achieve a lot in this world. This appreciation and this honouring have helped me make progress towards working for justice and the rule of law and have bestowed upon me a big responsible to fight for noble causes. This is done through promoting a culture of peace, unifying efforts in the service of justice, supporting legal and arbitration institutions and encouraging Arabs and others to tap into their potential on a global level.

You were nominated by Arbitrator Intelligence as Presiding Arbitrator of the Year in 2020. What is this award and how do you comment on this?

Among the hundreds of arbitrators in the world, Arbitrator Intelligence has chosen me to be the 2020 Arbitrator Intelligence Presiding Arbitrator.

Having started in the United States, this award aimed to foster transparency, accountability and diversity in selecting arbitrators by increasing access to critical information about arbitrators and their issuance of arbitral awards.

This annual award is issued after collecting and processing information on the performance of arbitrators in arbitral cases through its electronic platform. The data is treated in total confidentiality.

I have received positive feedback from losing parties and lawyers in several arbitration cases in which I sat as an arbitrator. Losing parties gave me positive feedback on my performance in these cases and praised the management and adjudication of cases as well as the granting of all the rights of defence. The evaluating parties also expressed their willingness to re-appoint me as arbitrator in future cases.

In recognition, I was granted the award. It was announced on the platform’s global website and social media platforms. This recognition only keeps me steady and determined to work in accordance with the values, principles and rules that are at the core of the legal and arbitration profession.

In Arab societies, women often suffer from difficulties in performing their work for various reasons. What are the main challenges and obstacles you overcame?

Since the second half of the twentieth century, there has been a growing awareness of the importance of women’s education in different fields, including law. The door was opened for women to continue their specialisation in international commercial law and to prove their competence and leadership qualities, especially in arbitration.

When I attended arbitration seminars in the 1990s, there were very few female presenters and the women pursuing post-graduate studies in international commercial law were not numerous. Today, things have changed. A greater number of female students specialise in arbitration, especially since it has become part of the academic curricula of post-graduate studies in many law faculties.

As for my own experience, when I decided to pursue legal studies with the aim of becoming a judge, my father warned that it would be challenging for a woman to make herself a name in this field, which was dominated by men. That was the first challenge for me. The second challenge was when I decided to be an arbitrator, not a judge empowered by the public authority. This was a first challenge for a Middle Eastern woman who decided to become an arbitrator, even though a small number of women had already authored valuable publications on arbitration, such as Samiah Rashid, Hafiza Hada, Hasiba Al-Qalyubi and others. The greatest challenge was that our culture gives power to the man, and it would be difficult to appoint a woman to settle domestic and international disputes and be trusted with this task as the women’s role is presumably limited to providing support without being the decision maker.

When I decided to work in this field, some of my friends advised, “Don’t go down this road. No man will marry you.” However, I refused to believe in this advice, and eventually met my husband who accepted the risk and we decided to build our family together.

I do admit that without the support of my husband and children and their acceptance of my role in life, I could not have succeeded in my career as an international arbitrator. In fact, I am honoured that my children, Ziad and Zeina, also chose the path of law and pursued a legal profession.

The placement of trust in a woman and the acknowledgement of her role in the business world did not come easy. On one occasion, I remember when my name was once proposed as president in a local arbitration, one of the arbitrators refused to have a woman chair the arbitral tribunal. A female arbitrator faces challenges. Imagine being required to have the freedom of movement and travel, being required to build a high professional reputation without losing her femininity and being required to assume at one-and-the-same time her roles of professional arbitrator, wife and mother. It requires that she put her career before her social life, and even before her family when necessary. Most of these matters are very sensitive.

Indeed, combining work and family life is an additional challenge. This may constitute an initial obstacle to seizing the opportunities in life, but I genuinely believe that women can manage their time and responsibilities for their family and their work in a balanced way.

In light of my experience, I would say that being a woman in arbitration is not the story of “men vs. women,” as it is not the story of “women from the West vs. women from the Middle East.” In fact, becoming an international arbitrator is a challenge in itself, be it for men or women, in the Middle East or anywhere else in the world.

Needless to say, much remains to be done at the national and international levels to ensure a change of mentality and gender equality. I believe the most important changes start within, especially for women themselves, along with men who support this development. Only then will we be able to raise awareness about the importance of this issue and make the image of female arbitrators much clearer in the arbitration world.

Dr. Nayla, today you set an excellent example for the youth who seek excellence and success in legal practice. What is the most important advice you give them?

After practising and teaching law for more than 40 years, my conviction only increased that there is a need to promote the knowledge and culture of international law in civil, common and Islamic law systems, especially in terms of promoting private justice, i.e. arbitration. I encourage young people to pursue their academic studies, because this is their greatest asset.

They ought to set ambitious goals and consistently aspire to perform with professional excellence. Challenges are inevitable, and one must continue with strength and determination, armed with professional ethics. The road to success requires diligent and continuous work. Success would only be a matter of time! Gebran Khalil Gebran says: “The value of a person is not measured by what they achieved but by what they seek.”

Last but not least, allow me to thank you and thank Arabisk London Magazine for hosting me. I wish you and the dear readers success and accomplishment.

You may like

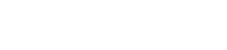

Lina Village: The Kingdom’s Well Site

Adeem Al-Fursan: A Novel Development Project in Riyadh

Ahmed Reyad, an Egyptian Face-Reading Expert: Personality Analysis Inspires Self-Improvement and Societal Change!

Saudi Arabia’s Cold Tourism in 2025

Humain, an AI Startup, is Launched in Saudi Arabia