Home » Interviews » Dr. Aala El-Khani: A humanitarian psychologist working globally

Interviews

Dr. Aala El-Khani: A humanitarian psychologist working globally

Published

3 years agoon

By

Huda Az

Dr. Aala El-Khani is a humanitarian psychologist working to support families globally.

Dr El-Khani works as a consultant for numerous international organisations, including the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC).

She was awarded a PhD in Clinical Psychology from the University of Manchester, where she is now an honorary Research Associate.

She has developed family skills resources for UNODC, as well as other international organisations and academic institutions, such as The University of Manchester, War Child and Chemonics International. Dr. El-Khani is a global master trainer of several international psychosocial, family skills, and trauma recovery interventions. She has led family skills training in over 20 countries including Uzbekistan, Senegal, Palestine, Indonesia and India.

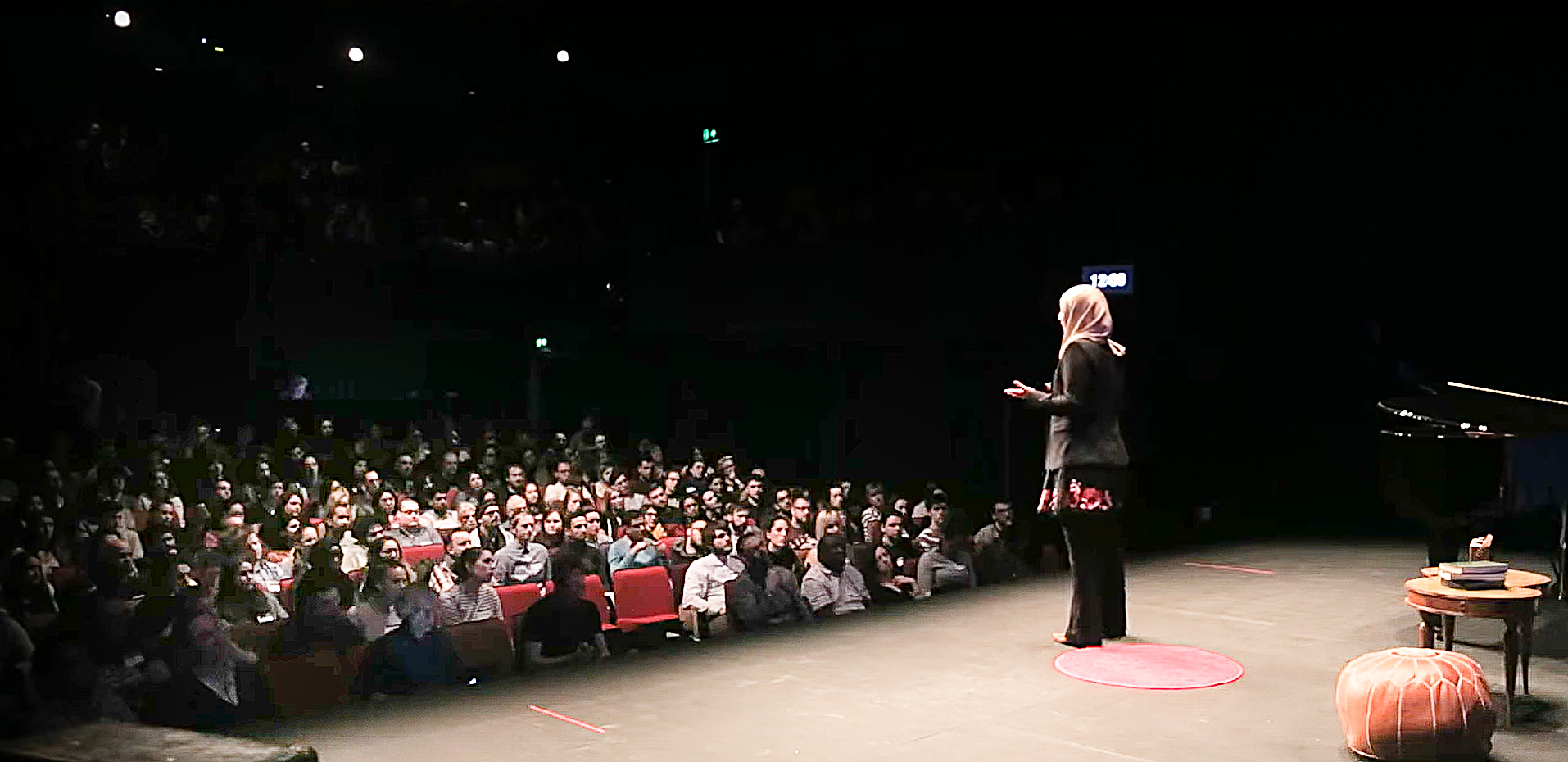

Dr. Aala has conducted research with families in refugee camps and conflict zones, exploring their parenting challenges and has gone on to develop family skills resources to meet their needs. Her work has significantly contributed to an agenda of producing materials for families affected by conflict, displacement and residing in low resource contexts. Dr. El-Khani’s work has been globally recognized, including receiving several prestigious awards. Her two TED talks have been viewed over 1.5 million times.

1. You have given many talks on prestigious stages, including at United Nations meetings and the TED stage. Your passion for your work is always so evident. Tell us more about your speciality and why you are so passionate about what you do.

I believe being a parent is one of the most important roles a person might play in their lifetime. But when children are born, they don’t come with a manual to help parents with this job. Much research tells us that the relationship a child has with their parent is the most important factor in their future wellbeing. This includes their mental health development, their academic achievement, their ability to form healthy adult relationships, and go on to have a good happy life.

Because being a parent is such an important job, all parents can greatly benefit from family skills programmes that teach key parenting principles.

Skills such as communicating positively through both listening and talking to our children, techniques to encourage good behaviour such as using praise and establishing family rules, spending time with them, and showering them with physical affection.

Good parenting skills also means setting healthy limits, so children feel secure and are safe.

Parents that make time to engage with parenting information have happier and healthier relationships within their families.

I work to develop resources that promote these key parenting principles that families need to thrive. I work on researching what families around the world need, developing and writing resources that address these needs, and then conducting training around the world to facilitators who implement these programmes within their communities.

2. You have conducted award winning research with refugees and have specialised in working with parents who have been through conflict and displacement. Do you believe families in humanitarian settings can be supported, despite the obvious challenges?

In humanitarian contexts, the role of the parent, or other primary caregiver when the parent is missing, is even further magnified. The quality of care that children receive in their families can be a more significant indicator of their mental health then from their actual experiences of war or displacement.

But families in humanitarian settings are incredibly vulnerable.

My research, at the University of Manchester, led me to spend time with families in refugee camps and highlighted that parents in these challenging contexts are experiencing their own emotional challenges.

They are focused on survival and trying to maintain basic family needs, such as food and shelter.

They are overwhelmed with changes in their children’s behaviours and emotions, and don’t know how to help them. Many parents I met were actively searching for information, but none was available. Meeting parenting needs for such information is commonly not recognised as a priority for aid agencies, and this is something I work passionately to change.

Colleagues and I at UNODC and the University of Manchester have worked to develop resources for families in such contexts. These range from leaflets, books, videos and longer multi-session programmes, all open access and free to ensure they can be easily accessed by those in need.

3.You have worked for several years as an international consultant for the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. How does this role parallel your work with family skills programmes and how can we prevent young people from dangers such as crimes and drugs?

Family focused interventions were highlighted by the ‘UNODC/WHO International Standards of Drug Use Prevention’. Substance use prevention strategies have called for a move in the response paradigm; to focus on the people rather than the substances themselves. This modality also fulfils the commitments expressed by Member States of the United Nations committed to engage in reaching the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) on the road to 2030.

Family focused interventions interlinks many of the 169 targets of the SDGs. As a result, UNODC has been availing many open-source, low-cost materials for parenting support designed for low- and middle-income countries.

I have had the privilege to be involved in co-developing a number of these resources including two multi-session family skills programmes, UNODC “Strong Families,” and “Family UNited”.

We have trained families globally on these programmes and observed significant improvements in parental adjustment and functioning and children’s resilience, behaviour and mental wellbeing.

As for how we can prevent young people in becoming involved in risky activities; increasing parents’ skills effectively prevents adolescent initiation of many risky behaviours, including substance abuse and criminal behaviour.

When parents engage in learning and implementing positive parenting skills, the result is a healthier and more supportive environment in which children can grow and develop.

Caregivers with enhanced parenting skills are more likely to have a healthy open relationship with their children which leads children to more likely choose friends who have similar family values and are a positive influence.

Youth resilience is crucial for not taking part in substance use and criminal behaviour. Resilience development is greatly promoted when caregivers support children to become independent and expect compliance with rules, while also being fair in their discipline practices.

4. Your name features as a co-author of several resources developed by the United Nations, including family skills resources for families to utilise during COVID-19. Do you believe COVID-19 has impacted families, and if so, how?

4. Your name features as a co-author of several resources developed by the United Nations, including family skills resources for families to utilise during COVID-19. Do you believe COVID-19 has impacted families, and if so, how?

Yes, I believe the spread of COVID-19 has changed family life. For parents whose children are often out of school, the stresses of parenting may be increased by juggling work and caring for children, plus worries about loss of income and illness. Isolation can of course be a golden chance for parents to spend more time with their children and develop their relationship with them, but many parents like myself, will have experienced conflicting feelings and priorities, as well as real practical challenges in caring for children while also working.

Caring responsive adults help protect children in difficult times, it helps children make sense of uncertain times and eases their anxieties and worries.

Along with my UNODC colleagues, we developed specific parenting tools, including leaflets, booklets, and videos of parenting information for families facing COVID-19 globally. These tools have been made available in over 35 languages and are being utilised globally.

I believe there is now more appreciation of the important role caregivers play in supporting their children.

As the world eases out of lockdown, I see there is more recognition that what our children need to thrive starts in our homes and the relationships we develop with our children.

5. In your experience working with families around the world, are there any family needs specific to Arab families in the Middle East?

I have found that, wherever I am working in the world, parents want the same things for their children; to be healthy, happy and safe. But certainly, every culture and every region may have certain family needs that need to be considered.

Commonly in the Middle East, families employ staff as domestic helpers to assist in household chores, but in reality are involved in a lot of childcare too, particularly for younger children.

Such employees may have little background in childcare and this can be detrimental to children’s development and emotional wellbeing.

For this reason, I provide clients in the Middle East with a personalized package of family skills support, including online training of the parents, nannies and domestic help workers working within families, to provide a complete cycle of support for parents and the staff they employ.

6. Dr. Aala, you have developed many interventions and resources. What is your latest highlight or activity?

Earlier this year, Chemonics International invited me to develop a support programme for Syrian refugee children in North-East Syria. Many have lived their entire lives under conflict and experienced multiple traumas. Others were born into refugee camp life and the associated harshness. Recognising that caregiver support, can be the most important protective factor for children’s wellbeing, I developed ‘Better Together’, a psychosocial family skills programme for children and their caregivers to learn and practice key skills together.

I trained wonderful facilitators inside Syria, who went on to implement the programme with hundreds of refugee families.

Research measuring the mental health and wellbeing of children and caregivers before and after the programme is very encouraging.

Children described overcoming terrifying nightmares, how they were now confident to share their feelings with their caregivers and ask for help, and how their parents were more understanding to their needs and many had stopped using physical punishment.

They also described a profound sense of hope for the future.

Likewise, parents described a renewed sense of confidence in their ability to understand and empathise with their children. They greatly welcomed the techniques to manage misbehaviour that helped them control their anger and not lash out at their children.

These changes indicate children who are far more likely to go on to have better future outcomes and better mental health, and less likely participate in violence, drug use or criminal behaviour. These are also children and caregivers who are more likely to break intergenerational cycles of violence.

7. Dr. Aala, you are an example for young people today to engage in the practice of humanitarian activities. What would you like to say to these young people?

The heart and the mind together produce the most magical combination. Think carefully about how you might be of service to others. What stimulates your mind and heart? What need can you identify that you can help meet? I believe this message is not just for youth though. We can all contribute to making a difference to those most vulnerable no matter what age we are.

Humanitarian work does not necessarily mean you must take a flight and help someone far away in need. We need to move away from this idea. Humanitarianism is the belief in the value of human life and trying to provide support to those in need. We can all do this every day, by serving those around us. I think, keeping this in mind, helps keep us be compassionate, regardless of what’s happening around us, and this makes us better people who can work to help others.

8.Your work takes you to many parts of the world. Tell us more about your experience travelling and training in different countries, and how you balance this with your role as a mother?

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, I was travelling to a new country to conduct UNODC family skills training, or take part in a meeting, almost every 6-7 weeks. This is a part of my job I particularly love. It is quite heart-warming to me to know I have participated in knowledge sharing, that I believe is so important, to many corners of the world.

As for balancing family and work life, I no longer measure this ‘balance’ on a day-to-day basis. A more wholistic approach where I am able to evaluate how I have spent my time over a week or month is much healthier for me. As a woman, it does often seem I have an extra hurdle to jump, but I use this as motivation to challenge me do my best for both my work and my family, rather than set me back.

The reality for my children is they have always had a mother who is passionate about her work. I am very open and honest with my children. When I make a mistake, I am quick to apologise to them. I tell them that just as I am watching them grow and change, they too are watching me evolve and mature as a parent. I ask for their ideas on the projects I am involved in, and I share the ups and downs. I hope my work adds value to their life and will shape them to be adults who engage in meaningful roles.

9. Finally, in one sentence, what is the one message you might share with parents?

The greatest gift we can give our children, or anyone we care about, is our time. Time is love.

You may like

Solitaire Riyadh: A Tour of an Elegance & Luxuriance World

Rawan Al-Hamidi: Balanced Opinion Pieces Demonstrate the Journalist’s Objectivity

Diriyah’s Popular Cafés: Art & Creativity Collide with Genuine Heritage

Saudi Football Documentation Project: Extensive Disputation

Nammos Resort AMAALA: KSA’s New Address for International Luxury Hospitality